Melanoma: Most Serious Type of Skin Cancer

Melanoma is the most serious form of skin cancer. In the United

States, it is the fifth most common cancer in men and women; its incidence

increases with age. As survival rates for people with melanoma depend on the

stage of the disease at the time of diagnosis, early diagnosis is crucial to

improve patient outcome and save lives. Although most melanomas are detected by

patients themselves, clinician detection is associated with thinner, more

curable tumors. Most patients with thin, invasive melanoma (Breslow thickness

≤1 mm) can expect prolonged disease-free survival and likely cure following

treatment.

Melanoma is a type of skin cancer that originates from

melanocytes, the cells responsible for producing melanin. It accounts for a

significant proportion of cancer-related morbidity and mortality worldwide.

This section provides an introduction to melanoma, its classification, and the

global burden of the disease.

The age-standardized annual incidence of melanoma worldwide is

estimated at 22 in 100,000 people and has been increasing in the past decades.

However, it is not clear to what extent this represents an increase in true

disease occurrence, or an increase in thin melanoma diagnosis due to greater

screening or change in biopsy rates or histopathologic diagnosis.

Most melanomas arise as superficial indolent tumors that are

confined to the epidermis, where they remain for several years. During this

stage, the horizontal or "radial" growth phase, the melanoma is

almost always curable by surgical excision alone. Melanomas that infiltrate

deep into the dermis are in a "vertical" growth phase and have

metastatic potential. A definitive diagnosis of melanoma is made by

pathological analysis of a biopsy of the lesion.

Melanomas occur in sun-exposed and in non-sun-exposed areas.

Non-sun-exposed melanomas are less readily detectable and less responsive to

available treatments due to differences in tumor biology between those in

non-sun-exposed and sun-exposed areas. Sun exposure is less of a risk factor

among darker-skinned persons.

Risk factors for melanoma incidence include genetic, phenotypic,

and environmental factors and are discussed in detail elsewhere.

In addition, there are also certain characteristics that place

patients at higher risk of dying from melanoma:

- Skin of color: Although there is a far lower incidence of melanoma among Black patients, the five-year relative survival is lower than for White patients (69 versus 93 percent). The same trends have been observed in the Hispanic American population, who have a low incidence of melanoma but demonstrate a growing burden of disease and greater likelihood of presenting with advanced disease compared with non-Hispanic White individuals. Greater mortality in patients with skin of color (e.g., skin phototypes IV to VI) may be due to delayed diagnosis due to a lower perceived risk of disease or lower rates of skin examinations, locations of melanoma in atypical non-sun-exposed areas (e.g., leg, hip, and feet), a higher proportion of acral and nodular subtypes, and a decreased ability to seek care for localized disease.

- White males over age 50: Nearly 50 percent of melanoma deaths in the United States occur among White men over age 50, and men in this age group have been found to have a higher risk of death due to melanoma than women in the United States, New Zealand, Australia, and the United Kingdom (particularly West Scotland). Poorer melanoma survival for men may be explained both by differences in tumor biology and by differences in skin awareness, self-examination, and other early detection practices.

Prevention and Screening

- No randomized trials have been conducted to establish the efficacy of screening for melanoma on mortality reduction, but observational studies evaluating the impact on tumor thickness or mortality are encouraging. Although the majority of melanomas are initially detected by patients themselves, melanomas detected by clinicians have consistently been shown to be thinner than those found by patients or their significant others.

- The harms of screening for melanoma include the potential that false-positive findings on skin examination will lead to an increased number of dermatology referrals and unnecessary biopsies, with resulting anxiety, scarring, and expense, and the possibility of overdiagnosis (ie, the diagnosis of melanoma that is either non-growing or so slow-growing that it would never become clinically meaningful during the patient’s lifetime).

- Patients with certain risk factors are at high risk of developing or dying from melanoma:

- White adults age 50 and above.

- Total nevus count above 50 and/or presence of large (atypical/dysplastic) nevi.

- Personal history of skin cancer.

- Immunosuppression, particularly chronic use of immunosuppressive medications such as those used by organ transplant recipients.

- Very sun-sensitive individuals and those with “red hair phenotype” (eg, light skin pigmentation, red or blond hair color, high-density freckling, and light eye color [green, hazel, blue]).

- Family history of melanoma in one or more first-degree relatives or in more than one second-degree relative on the same side of the lineage. Those with at least three affected members (including one or more first-degree relatives) on one side of the family are at very high risk.

- For high-risk patients, we suggest screening for melanoma (Grade 2C). Screening involves a full-body skin examination performed yearly by a clinician who has had appropriate training in the identification of melanoma (clinician examination) as well as education for patients about melanoma risk factors and advice to alert their clinician if self-examination detects changing moles or other suspicious skin lesions.

- For the general population outside of these high-risk groups, we do not routinely screen with clinician skin examination. However, for patients without identified increased risk, clinicians should remain vigilant for any suspicious lesions identified in the course of a routine or sick visit (opportunistic case finding). A focused skin examination of the palms, soles, and digits may be of value in people with darker skin, who are more likely to have acral melanoma. All patients should be aware of melanoma clinical warning signs and bring any concerning lesions to the clinician’s attention.

- Certain tools can help clinicians and patients identify lesions to evaluate further for melanoma. These include the "ugly duckling" sign, the ABCDE rule of melanoma, and the Glasgow revised seven-point checklist. Further detail is provided elsewhere. Detecting melanoma in children is discussed separately.

- When suspicious lesions are detected, appropriate referrals are warranted (to a dermatologist where possible) for further evaluation of all such lesions.

- All patients should be educated about the importance of sun protection for melanoma prevention.

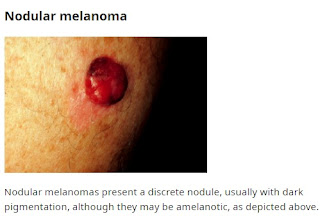

.jpeg)

Comments

Post a Comment